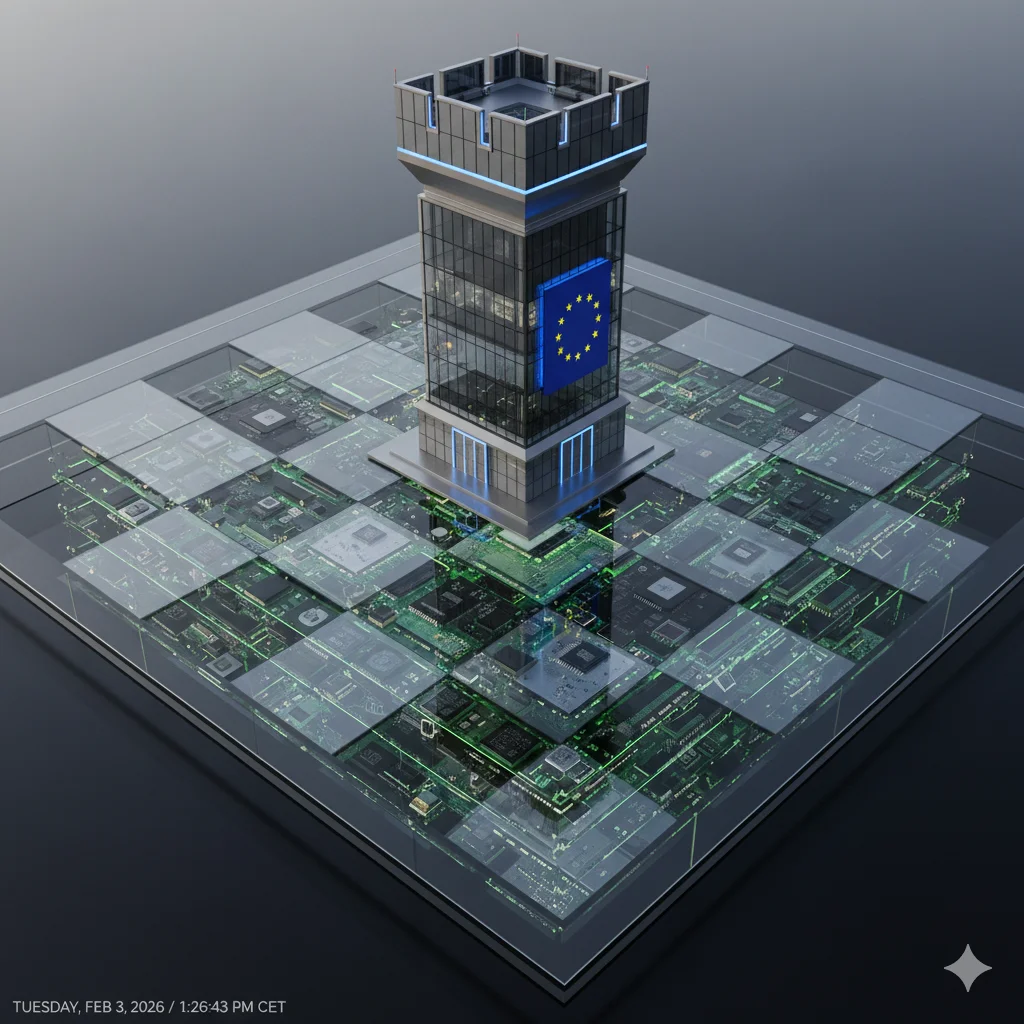

The European Commission is expected to propose the Cloud and AI Development Act (CADA) in Q1 2026. If you work in European tech, cloud, or AI, this will affect you.

CADA appears to be a serious attempt at European cloud sovereignty. However, it’s walking into a graveyard of predecessors with similar ambitions who failed spectacularly.

What CADA actually is

CADA is a legislative initiative. Not a voluntary framework, not a set of guidelines, not another half-baked GAIA-X. It’s built on Article 114 TFEU (internal market harmonization), which means it would be a binding regulation with direct effect across all member states. That alone distinguishes it from most prior work.

The initiative emerged from the AI Continent Action Plan, announced by Ursula von der Leyen and placed under Executive Vice-President Henna Virkkunen’s Tech Sovereignty portfolio. The public consultation ran from April to July 2025. The European Council explicitly asked the Commission to “be ambitious” in its October 2025 conclusions.

The Commission’s consultation document structures CADA around three pillars. Each addresses a different failure mode of European cloud policy.

Pillar 1: Research and innovation in resource-efficient infrastructure

This is the long-horizon bet. The premise is simple: Europe can’t outspend the US and China on data center scale, so it should try to out-engineer them on efficiency. The Commission wants to fund R&D in AI-optimized hardware, smarter power management, and methods to distribute AI workloads across smaller, distributed facilities rather than concentrating everything in massive hyperscale campuses.

Why efficiency? Because the energy bill is becoming the binding constraint. The International Energy Agency projects global data center electricity consumption will more than double from around 415 TWh in 2024 to 945 TWh by 2030. European energy costs are structurally higher than in the US or China. If you can make an AI workload run on half the electricity, you’ve effectively halved one of Europe’s biggest competitive disadvantages.

The question is whether Pillar 1 amounts to a genuine strategic bet or an expensive fig leaf. Europe has pockets of real strength — photonics research in Eindhoven, neuromorphic computing at Intel’s Irish labs and several EU universities, energy-efficient inference work at institutions like CEA in France. But translating academic excellence into commercial products is exactly where European industrial policy keeps stumbling. The European Court of Auditors assessed the comparable R&D pillar of the EU Chips Act in 2025 and concluded that it would not achieve its target of a 20% share of the global semiconductor market. Their recommendation: “an urgent reality check.” Investment is insufficient, and success depends on member state action, private-sector follow-through, and external factors beyond the Commission’s control.

For Pillar 1 to matter, the Commission would need to place concentrated bets on areas where Europe has a plausible path to differentiation rather than spreading funding thinly across a broad R&D agenda. The track record suggests the latter is more likely.

Pillar 2: Creating the conditions for data center investment

Here’s where the numbers get uncomfortable. Despite comparable GDP, the United States has roughly twice Europe’s share of global data center capacity. Three US-based companies — AWS, Microsoft, and Google — account for roughly 70% of the EU cloud market.

The trajectory is going in the wrong direction. European cloud providers’ collective market share fell from 29% in 2017 to around 15% today, even as their revenue roughly tripled in that period. They’re running faster and falling further behind.

CADA’s answer is to triple EU data center capacity within five to seven years. The concrete mechanisms under discussion include harmonized fast-track permitting across member states (currently fragmented and often painfully slow), strategic grid integration for energy access, and capital support for new European market entrants through the proposed European Competitiveness Fund.

In its consultation response, Microsoft cited Aragon in Spain as a model: a single, streamlined permitting process with fast-track procedures for strategic projects. When Microsoft is telling you how to make it easier for Microsoft to build data centers in your jurisdiction, you should listen carefully — and then ask who actually benefits.

Finland’s government was more direct: action is needed to ensure “the benefits of building data center capacity do not primarily flow to actors outside the EU.” This is the core tension in Pillar 2. If you streamline permitting and reduce energy costs for data centers, the primary beneficiaries — given the current market structure — will be AWS, Azure, and GCP. They have the capital. They have the operational expertise. They have the customer base.

So Pillar 2 faces a paradox: building infrastructure that primarily benefits the companies you’re trying to reduce dependence on. Unless Pillar 3 changes the equation.

Pillar 3: Highly secure EU-based cloud capacity

This is where CADA will succeed or fail.

The third pillar focuses on ensuring that “a set of narrowly defined highly critical use cases can be operated using highly secure EU-based cloud capacity.” The critical use cases stakeholders have identified include defense, public administration, and critical infrastructure.

The key challenge is defining what “highly secure EU-based” actually means. And here, Europe has a history of getting this wrong. The European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for cloud services (EUCS) has been deadlocked since 2019 over whether to exclude non-EU providers from the highest certification levels. Six years of negotiation, no agreement, no scheme.

CADA is expected to revive this conversation and cut the Gordian knot by building sovereignty requirements directly into legislation rather than leaving them to a voluntary certification process. The Commission recently published a Cloud Sovereignty Framework linked to its procurement of sovereign cloud services for EU institutions, with assurance levels requiring that technology and operations be under complete EU control and subject only to EU law.

This framework is already shaping the debate. Dassault Systèmes has advocated requiring cloud providers to be headquartered in the EU. SAP argues existing certification frameworks are sufficient. France and Germany recommend using public procurement mandates to drive the emergence of competitive EU solutions. Microsoft, predictably, has called for the EU to avoid measures that would “discriminate against non-EU actors,” citing WTO obligations.

The stakes are sharpened by the US CLOUD Act, which explicitly asserts extraterritorial jurisdiction — authorizing US authorities to compel US companies to produce data “regardless of whether such communication, record, or other information is located within or outside of the United States.” A US hyperscaler can build a data center in Frankfurt, staff it with German citizens, encrypt everything with keys held by a French company, wrap it in an EU-incorporated joint venture — and the parent company in Seattle or Redmond still falls under US jurisdiction. To date, no major data disclosures to U.S. authorities under the CLOUD Act for European customers have occurred (Don’t ask about FISA? By design, we’ll never know). But whether that makes it a manageable practical risk or an unacceptable structural exposure depends on your threat model — and for defense, classified government systems, and critical infrastructure, most EU member states have concluded it’s the latter.

What this means for hyperscalers

The impact on AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud depends entirely on how aggressively Pillar 3 lands.

Scenario 1: Strict sovereignty.EU-headquartered providers only for critical public sector workloads. This is France’s preference and aligns with the maximum assurance level in the Commission’s Cloud Sovereignty Framework. It would lock hyperscalers out of the most symbolically important (if not revenue-significant) government contracts and create a protected market for OVHcloud, Scaleway, IONOS, and others.

Scenario 2: Qualified sovereignty.Hybrid arrangements in which hyperscalers participate through joint ventures with EU partners that meet operational requirements: EU-based staff with security clearances, encryption under EU control, and no exposure to US extraterritorial law. Italy’s public administration already operates this way—hyperscalers can provide services at the highest criticality when- encryption and operational requirements are met. This is where Microsoft’s Bleu (with Orange and Capgemini, in France), GCP’s S3NS (with Thales, in France), Delos (with SAP, in Germany), and AWS’s brand new €7.8 billion European Sovereign Cloud in Germany are pre-positioned.

Scenario 3: Sovereignty washing.Requirements that can be met by hosting servers on EU soil — essentially what exists today. Hyperscalers invest in “sovereign” branding, satisfy checkbox compliance, and make no structural changes.

The realistic read: the political appetite is for something between Scenario 1 and Scenario 2. The European Council asked for ambition. Emmanuel Macron and Friedrich Merz jointly endorsed EU-wide definitions for sovereign cloud at the Berlin Digital Sovereignty Summit. The geopolitical context — Trump 2.0, CLOUD Act tensions, the Greenland rhetoric — has made digital dependence on the US politically toxic in a way it wasn’t even two years ago.

But the hyperscalers have been reading the room for a while. They’ve adapted before, and chances are they’ll adapt again.

Why history says be skeptical

Professor Antonio Calcara at Vrije Universiteit Brussels argues that in EU cloud policy, “failure at the EU level is designed to lead to national success” — member states use EU-level progress to strengthen their individual bargaining positions with US hyperscalers rather than collectively building alternatives. The EU framework becomes a negotiating lever, not a market-building instrument.

That pattern is depressingly consistent.

CloudWatt and Numergy (2012).France’s €150 million national cloud champions. Both failed within five years. They couldn’t attract customers or match hyperscaler scale.

EUCS (2019).Deadlocked for six years over the exact sovereignty requirements, CADA is now trying to legislate. Member states cannot agree on whether to exclude non-EU providers from the highest assurance levels.

GAIA-X (2020).Launched as the “Airbus of the Cloud” by France and Germany. Was supposed to create a federated European data infrastructure. What happened? The initiative admitted AWS, Microsoft, and Google as members. Nextcloud CEO Frank Karlitschek called it a “paper monster.” Scaleway, a founding member, withdrew. European cloud market share continued to decline throughout GAIA-X’s existence.

IPCEI-CIS (2023).€1.2 billion in public funding across seven member states. Produced one operational sovereign edge cloud platform (virt8ra — ever heard of it?). The gap between investment and output is striking.

And while Europe negotiates with itself, the competition for global AI workloads is coming from directions Brussels didn’t anticipate.

Meanwhile, in New Delhi

While I was writing this post, India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman dropped a bombshell in the annual budget: zero taxes through 2047 on revenues from cloud services sold outside India, provided those services run from Indian data centers. Read that again. A 21-year tax holiday for any cloud provider willing to build AI infrastructure on Indian soil and serve global customers from there.

This isn’t an abstract policy aspiration. The hyperscalers are already all-in. Google committed $15 billion to build an AI hub and expand data center infrastructure in India — its largest commitment in the country to date. Microsoft followed with $17.5 billion by 2029 for AI and cloud expansion. Amazon added $35 billion by 2030 on top of $40 billion already invested. On the domestic side, a Reliance-Brookfield-Digital Realty joint venture is investing $11 billion in a 1-gigawatt AI-focused data center campus in Andhra Pradesh. Adani Group is committing up to $5 billion alongside Google to a new AI data center project.

India has real constraints — patchy power availability, water scarcity, and state-level permitting bottlenecks. But the signal is unmistakable: while Europe debates definitions of sovereignty and layers on regulatory requirements, India is competing for the same global AI workloads with raw economic incentives at a scale Europe can’t match.

This matters for CADA in two ways. First, it exposes the competitive asymmetry of Europe’s approach. CADA’s Pillar 2 aims to create “the right conditions for investment in data centers.” India just created conditions that make European incentives look timid by comparison. The US offers a 100% immediate capital expense deduction for data center equipment under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. India offers zero taxes for two decades. Europe offers harmonized permitting and, potentially, capital from the European Competitiveness Fund. When AWS and others are deciding where to build their next gigawatt of AI compute, the math is not subtle.

Second — and this is the part that should keep CADA’s architects up at night — it complicates the sovereignty narrative itself. The implicit assumption behind European cloud policy is that the fight is between European providers and US hyperscalers, with workloads that should “naturally” reside in Europe. But if India successfully attracts the next wave of global AI training and inference workloads with zero-tax economics and a massive engineering talent pool, Europe isn’t just losing to Silicon Valley. It’s also losing to Hyderabad and Visakhapatnam. Sovereignty becomes an academic exercise if the workloads were never going to be in Europe in the first place.

The unresolved contradictions

Regardless of its ambitions, CADA cannot succeed unless the EU resolves several fundamental tensions.

The energy trilemma

CADA aims to triple data center capacity within five to seven years. The EU simultaneously aims to reduce final energy consumption by 11.7% by 2030, achieve carbon neutrality for data centers by 2030, and deliver on the Green Deal. These goals are in direct conflict.

EU data center power demand was approximately 70 TWh in 2024. The IEA projects 115 TWh by 2030; Ember’s analysis is more aggressive at 168 TWh. McKinsey estimates data centers could account for up to 25% of new net electricity demand in Europe by 2030 — and that’s before CADA’s tripling target kicks in.

The grid is already buckling: Dublin and Amsterdam have imposed moratoriums on new data center construction because local grids are at capacity. In Ireland, data centers consume 22% of the national electricity supply. Germany’s Energy Efficiency Act imposes the strictest requirements in Europe — 100% renewable electricity by January 2027, mandatory waste heat reuse, PUE caps — but these add cost and time to every project at the exact moment CADA wants to speed things up. The Nordics offer a partial escape route with uncongested grids and cold climates, but the fundamental arithmetic remains: if you condition fast-track permitting on strict green requirements, you slow down capacity deployment; if you don’t, you undermine the Green Deal. The IEA projects European capacity will grow by only 70% by 2030, well short of the tripling target. Something has to give.

The sovereignty paradox

Member states say “sovereignty” and do “bilateral.” France champions EU cloud sovereignty while simultaneously building Bleu (Microsoft + Orange + Capgemini) and S3NS (Google + Thales) — joint ventures that leverage US hyperscaler technology within French legal structures. Germany does the same with Delos (Microsoft + SAP). These national solutions may be pragmatic, but they undermine the collective European alternative that CADA ostensibly promotes.

The investment gap reinforces this. Amazon spent over $100 billion in capex in 2025, the vast majority of which went to AWS infrastructure. The entire EU cloud sector combined cannot match this. Public funding can help, but it cannot close a gap measured in hundreds of billions of dollars. The Chips Act demonstrated the limits of public funding amid structural market dynamics.

The regulatory weight problem

CADA joins GDPR, AI Act, DMA, DSA, Data Act, NIS2, Cyber Resilience Act, and the pending EUCS. The Commission simultaneously promotes CADA and a “digital fitness check” to simplify existing rules — contradictory signals that aren’t lost on the 55% of SMEs who cite regulatory complexity as their greatest challenge. Every new regulation has a compliance cost. At some point, the cost of complying with sovereignty rules exceeds the benefit of operating in the European market, and that’s when you get regulatory arbitrage rather than regulatory advantage.

The elephant in the server room

This is the contradiction CADA doesn’t address. Every “sovereign” European AI factory, every EuroHPC Gigafactory, every OVHcloud rack, and every Scaleway cluster runs on NVIDIA GPUs fabricated by TSMC in Taiwan. NVIDIA holds roughly 80% of the AI data center accelerator market. There is no European alternative. Not one.

Europe’s semiconductor manufacturing share has fallen to about 9% of global production today. The EU Chips Act set a 20% target by 2030. The European Court of Auditors projects the EU will reach 11.7% at best — and that’s mostly in automotive and industrial chips, not the AI accelerators that matter for CADA’s ambitions. Peter Wennink, former CEO of ASML (Europe’s crown jewel in the semiconductor value chain), called the 20% target “totally unrealistic.”

The European Processor Initiative’s Rhea1 — the continent’s first indigenous HPC processor — is based on ARM architecture. ARM is a UK company owned by SoftBank. The servers housing these processors are mostly assembled by companies in Taiwan and other parts of Asia. The networking equipment connecting them is predominantly from US vendors. Even Nebius, arguably Europe’s most promising sovereign AI infrastructure play, builds its racks around NVIDIA Blackwell GPUs.

The irony is hard to miss. NVIDIA itself is marketing “sovereign AI” to European governments, deploying 20 AI factories across the continent, including a 10,000-GPU industrial AI cloud in Germany operated by Deutsche Telekom. When France builds sovereign AI capacity with Mistral AI, the first phase deploys 18,000 NVIDIA Grace Blackwell systems. Every single GPU purchased for European sovereignty is revenue for Santa Clara.

CADA can regulate where data is stored, who operates the infrastructure, and which legal jurisdiction applies. It cannot change the fact that the entire compute layer — the part that actually does the AI work — is designed in California, fabricated in Taiwan, and assembled in Asia. Until Europe has indigenous AI silicon (and that’s a decade away at best, if it happens at all), “sovereign cloud” means sovereign software running on someone else’s hardware. That’s a meaningful but incomplete form of sovereignty, and CADA should be honest about the boundaries of what it can achieve.

Capacity isn’t the real problem

The Draghi report identifies energy and real estate costs as EU disadvantages, but US hyperscalers pay the same costs when they build in Europe — and they build anyway because the returns justify it. The real European disadvantage isn’t data center capacity. It’s the absence of complementary platform services, software ecosystems, and business services that make a cloud provider sticky. You can triple data center capacity and still lose market share if you don’t build the platform layer on top of it. CADA’s capacity focus may be solving yesterday’s problem.

The narrow path to success

Despite all of this, there is a version of CADA that could work—but it requires a level of political commitment and execution discipline that Europe has never demonstrated in digital policy.

In my opinion, it would look something like this: Pillar 3 lands between Scenario 1 and 2, with clear, enforceable definitions that create a genuinely protected market for critical workloads. Member states back those definitions with binding procurement mandates, not aspirational targets, but real euros flowing to EU-qualified providers. The European Competitiveness Fund provides sufficient capital to enable two or three European providers to build credible platform layers, not just raw infrastructure. And the Commission resists the temptation to water down requirements when a U.S. trade representative calls.

The success metric is simple: Does the market share trajectory of European cloud providers reverse? Every predecessor initiative failed on this metric. CADA has better structural foundations than any of them — binding legal force, concrete capacity targets, procurement mandates that create guaranteed demand, and a geopolitical context more favorable than at any point in the last decade.

Whether that’s enough depends less on the legislation itself and more on whether member states actually back EU alternatives with their procurement euros — or continue cutting bilateral deals with hyperscalers while championing sovereignty in Brussels. And of course, on whether the EU Commission is actually capable of anything at all.

The bottom line

The formal proposal is expected in Q1 2026. I’ll be watching it closely—and capital flows to India and GCC countries even more closely. If the EU drops the ball once more, that’s where the real fight will be.

Julien

Sources and further reading:

India offers zero taxes through 2047 to lure global AI workloads (TechCrunch, Feb 2026)

IEA: Overcoming energy constraints is key to delivering on Europe’s data centre goals (Nov 2025)

Ember: Grids for data centres — ambitious grid planning can win Europe’s AI race (Jun 2025)

Germany’s Energy Efficiency Act (EnEfG) — data center requirements (White & Case)